A Game Theoretic Analysis of the Brexit by the London School of Economics and Political Science

Let's hear it from the LSE:

Not punishment or revenge, but stone-cold sober calculations: the EU will drive a hard bargain

Having triggered Article 50 of the EU Treaty, the British government officially kicked off the Brexit negotiations on March 29. Until today, both parties pretended not to give in and instead promised a tough negotiation strategy. Game theory offers one way of testing the reliability of these claims and allowing the negotiations to be seen for what they are: a strategically driven, tactical game in which each side attempts to realise their own interests, write Berthold Busch, Matthias Diermeier, Henry Goecke, and Michael Hüther.

From the perspective of game theory, the search for the optimal negotiation strategy for the UK’s exit from the EU can be stylised as follows: both players, the UK and the EU, simultaneously choose between only two negotiation strategies – one compromising and the other uncompromising. This limitation is plausible in view of the fundamental need for each negotiating partner to describe a starting position. Here there are only the two corner solutions: ‘unwillingness to compromise’ and ‘willingness to compromise’. Furthermore, we assume that the negotiations will be mainly conducted on the following three topics:

- Access to the European single market

- Free movement of people

- Payments to the EU

The negotiations on the payments to the EU include contributions to the EU budget as well as EU claims against the UK – for example, arising from previous British commitments to contribute to EU employees’ pensions.

What are the stylised outcomes?

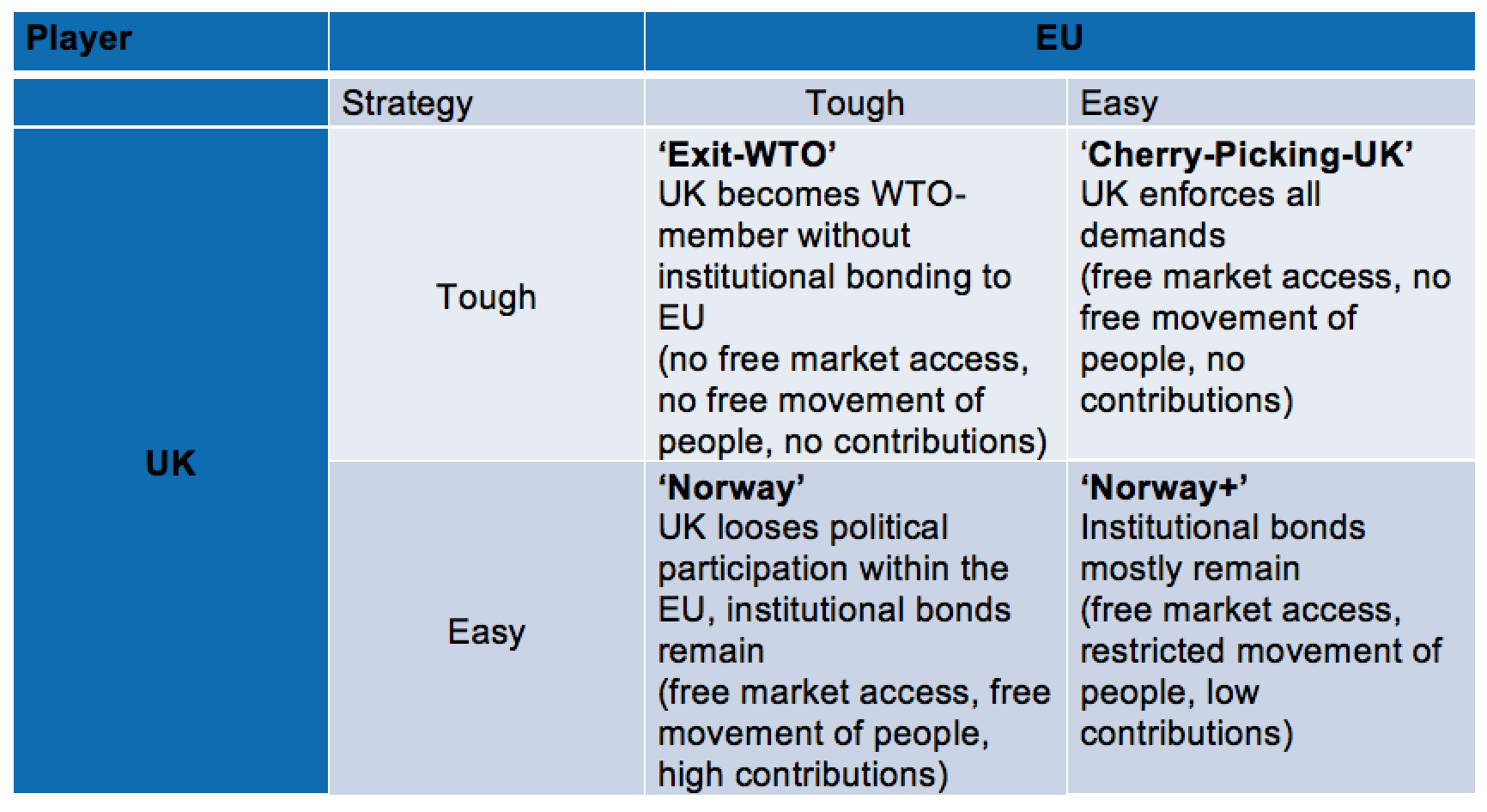

The different negotiation strategies and topics result in the game theory table that is shown in Figure 1 with the four possible results:

- World Trade Organisation (WTO) exit: If both the British and Europeans are uncompromising, then the British will completely lose access to the European single market. Economic cooperation would then be organised in the same way as it is with other WTO members. In this case, the British would not have to grant EU citizens free movement of people or make payments to the EU. The most clearly touted goals of Brexit advocates would be achieved, but the price would certainly be high: a complete loss of economic integration with a status as a WTO member that would still have to be negotiated.

- Cherry picking: On the other hand, if the UK conducts tough negotiations and the EU is willing to make concessions, the UK could have its demands fully met. In the case of this ‘cherry picking’, the EU would grant its partner full access to the single market without the need to impose the free movement of people or demand payments in return.

Figure 1: Brexit negotiations as a strategic game

Source: Busch et al. (2016)

- Norway: A Norway-style deal would result if the British are willing to compromise and the EU unyielding. Norway grants EU citizens full freedom of movement and makes payments to the EU. In return, the country has access to the EU single market, but it does not have any say in political decision-making. Norway’s contribution to economic and social cohesion policy in the EU between 2014 and 2021 amounts to almost €400 million per year. Given that Britain’s GDP is six to seven times the size of Norway’s, this would mean a hypothetical contribution of around €2.5 billion per annum. Based on the population size, the UK could even end up with payments of €5 billion per annum. That would be a high price: Britain’s average net contribution between 2010 and 2015 was around €9.4 billion per annum. According to a Commons study, the British contribution to a ‘Norway’-style deal could be even higher (House of Commons Library, 2013).

- Norway+: If both parties were willing to compromise in the negotiations, a so-called ‘Norway+’ deal could result. Britain would then be in a similar but more comfortable situation than Norway is today. It would have to contribute less financially, would not have to guarantee the full freedom of movement of people and would have unlimited access to the EU single market, but it would have no say in political matters. The EU would accept virtually all of Britain’s wishes and a new understanding of European integration. The negotiations would be purely technical in order to implement the British stipulations.

The long-term payoffs

In the ‘WTO exit’ solution, the EU and Britain would each lose an important free trade partner with which they currently carry out a great deal of seamless trade. Minis produced in Oxford, for example, would have a whopping surcharge of 10% imposed on them when they are imported into an EU country. According to a statement by the Director-General of the WTO, British exporters would have to fork out up to £5.6 billion annually. Furthermore, the search for the best staff in Europe would be increasingly complicated and bureaucratised. In British industry, one in every ten employees is currently from the EU, even more than in the international financial sector. Moreover, in the event of the ‘WTO exit’ solution, the latter would be faced with the loss of important banking licence rights that currently allow British banks to offer financial services in EU countries without any bureaucratic obstacles (passporting). According to a study by the City of London, this would lead to a direct loss of some 70,000 jobs in the London financial sector (Wyman, 2016).

In the long term, the British would probably conclude free trade agreements with third countries, but the new frictions on the markets for goods, services, employees and capital would remain in place. Ultimately the British would lose free access to at least 27 national economies, while EU countries would only lose free access to one. The EU’s tough negotiating tactics, as well as the negative economic consequences, would reduce the incentives for Brexit copycats in the long term.

The implications of the ‘cherry picking solution’ are entirely different. The smooth trading of goods and services could continue, the passporting rights of Britain’s financial industry would not be in danger and the Treasury could use the net payment to the EU of almost €9.4 billion per year for different purposes. Only restrictions on the free movement of people would have a negative impact on Britain’s potential in the long term: however, given the current discussion, no short-term mass layoffs of EU workers are to be expected. If the British government could achieve such a negotiation outcome, it would probably be revered at home. Having access to the single market without the free movement of people and no further payments to the alleged bureaucrats in Brussels would mean the ‘Brexiteers’ had achieved all their demands. While the single market may be secured in a more limited economic understanding (Pisani-Ferry et al. 2016), renouncing the four fundamental freedoms – the European standard since the 1957 Treaty of Rome – would represent a gambling away of the political idea of European integration to simple economic reasoning.

In the ‘Norway’ solution, the British would have to accept what they voted to end: the free movement of people. One of the most popular slogans of the Leave campaign – ‘take back control of immigration” – was based on the fear of migration flows. A ‘Norway’ solution would prove these promises illusory. Furthermore, payments of between €2.5 billion and almost €5 billion could continue to flow towards Brussels. According to a study by the Treasury, the growth prospects would in the long term decrease by around 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points annually in a favourable scenario similar to the ‘Norway’ solution (HM Treasury, 2016). Moreover, European legislature would act without any British participation. For the EU’s economies, this would have hardly any direct economic implications.

If both players were willing to compromise, the UK would end up with a ‘Norway +’ solution. In the long term, the British could significantly reduce their annual net contribution to the EU budget of around 0.5% of GDP. Combined with the approximate 0.2 to 0.3 percentage point decline in GDP growth, the overall effect for Britain would be roughly neutral (HM Treasury, 2016). In addition, this negotiation outcome would probably attract a number of individual imitators. The threat of uncompromising negotiations on the EU’s part would still be credible when compared to ‘cherry picking’. The Europeans have shown themselves to be open to compromise, but only in response to a similar willingness on the part of the British. The EU could always claim to opt for an uncompromising bargaining position if Britain proves to be unwilling to compromise during the negotiations. It is unlikely that many countries would trade political dependency without any participation for slightly restricted freedom of movement and a discount on contribution payments. However, countries like Norway would be predestined to negotiate better conditions.

Image (Wikimedia Commons), licenced under Public Domain.

Game theory equilibria: on the way to Norway

The game theory approach shows that the optimal response for the EU in the long term would be an uncompromising negotiation strategy, irrespective of the negotiating position taken by the British government: the EU would be better off with the ‘WTO exit’ solution compared to the others. The uncompromising negotiation approach is, therefore, a so-called dominant strategy, which would be rational for the EU to follow in the long term.

Regardless of the EU’s strategy, in the long term, it is always better if there is willingness to compromise. The long-run Nash equilibrium model therefore equates to the ‘Norway” deal. This settlement does of course run contrary to the wishes of Brexit advocates, and would lead to vehement reactions within the UK. One can also argue that the EU’s red line for a possible compromise outweighs Britain’s own red line, because the British are ultimately more dependent on the EU than vice versa. The asymmetry, which already existed before the negotiations, is clearly evident here.

The extent to which economic interests play a role in the negotiations is difficult to assess – political motives could overshadow the economic ones. However, in the long run allowing a soft Brexit with cherry-picking could inspire others to follow suit. The threat of uncompromising EU negotiations would have been proven to be an empty one and other countries would seek a similar result. After a potential departure of an important member state like France or the Netherlands, the EU would come to an end, signalling the failure of the European project. There would be massive economic upheaval in the EU, as well as in the UK. Allowing the UK to cherry-pick its way into a privileged institutional setting with the EU – although it might seem economically reasonable in the short-run – is unfeasible for the cohesion within the community of states, and therefore also for the British.

The achievements of the EU cannot be sacrificed for short-term economic interests. It is not about punishment or revenge, but about stone-cold sober calculations. The EU has to play a tough game and hope for a British Norway.

This essay is based on a paper first published in Wirtschaftsdienst, Volume 96, 12, page 883-890; an English version was published in IW Policy Paper 18, and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

Dr Berthold Busch is a senior economist at the Cologne Institute for Economic Research`s (IW Köln) research unit International Economics and Economic Outlook

Matthias Diermeier is a personal scientific assistant to the director of IW Köln

Dr Henry Goecke is a personal scientific assistant to the director of IW Köln

Prof. Dr Michael Hüther is the director of IW Köln

Comments